Gallery 844

Mythologies

(Part 1 of 3)

|

|

In 1957, a French philosopher

named Roland Barthes wrote an essay on why people love wrestling performances.

Barthes was interested in the signs and symbols used in pop culture to

spread a group's beliefs, attitudes, and morals.

|

|

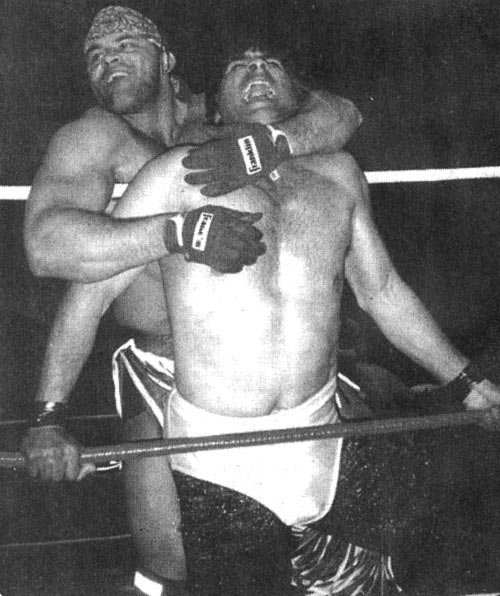

Barthes believed that people

get into the drama of Pro Wrestling because the clear, obvious scenes

of Suffering, Justice, and Defeat are easier to grasp (and therefore more

pleasurable) than real life, which is never straight-forward. This

is similar to dramatic theater popular in the olden days.

|

|

In the first part of

his essay, Barthes decribes how the actions and even the bodies of the wrestlers

send specific, very clear messages to the audience that draws them into the

world of wrestling. Here is the first part of his essay:

|

|

THE WORLD OF WRESTLING

by Roland Barthes, 1957

The grandiloquent* truth

of

gestures on life's

great

occasions.

--

Baudelaire

* [Grandiloquent means lofty,

over-blown; pompous, over-the top, kind of like Baudelair's poems.]

|

|

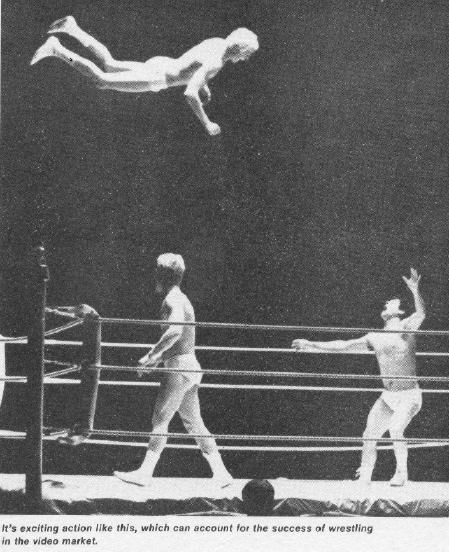

The virtue of wrestling

is that it is the spectacle of excess. Here we find a grandiloquence

which must have been that of ancient theaters.

|

|

And in fact wrestling is an

open-air spectacle, for what makes the circus or the arena what they are

is not the sky (a romantic value suited rather to fashionable occasions),

it is the drenching and vertical quality of the flood of light.

|

|

Even hidden

in the most squalid Parisian halls, wrestling partakes of the nature

of the great solar spectacles, Greek drama and bullfights: in both, a

light without shadow generates an emotion without reserve.

|

|

There are

people who think that wrestling is an ignoble sport. Wrestling is not

a sport, it is a spectacle, and it is no more ignoble to attend a wrestled

performance of Suffering than a performance of the sorrows of Arnolphe

or Andromaque. [Characters from two old tragedies.]

|

|

Of course, there exists a false

wrestling, in which the participants unnecessarily go to great lengths to

make a show of a fair fight; this is of no interest.

|

|

|

True wrestling, wrongly called

amateur wrestling, is performed in second-rate halls, where the public

spontaneously attunes itself to the spectacular nature of the contest,

like the audience at a suburban cinema.

|

|

Then these same people wax

indignant because wrestling is a stage-managed sport (which ought, by

the way, to mitigate its ignominy).

|

|

The public is completely uninterested

in knowing whether the contest is rigged or not, and rightly so; it abandons

itself to the primary virtue of the spectacle, which is to abolish all

motives and all consequences: what matters is not what it thinks but what

it sees.

|

|

This public

knows very well the distinction between wrestling and boxing; it knows

that boxing is a Jansenist sport, based on a demonstration of excellence.

One can bet on the outcome of a boxing-match: with wrestling, it would make

no sense.

|

|

A boxing match is a story which

is constructed before the eyes of the spectator; in wrestling, on the contrary,

it is each moment which is intelligible, not the passage of time.

The spectator is not interested in the rise and fall of fortunes;

he expects the transient image of certain passions.

|

|

Wrestling therefore demands

an immediate reading of the juxtaposed meanings, so that there is no need

to connect them. The logical conclusion of the contest does not interest

the wrestling-fan, while on the contrary a boxing-match always implies

a science of the future.

|

|

|

In other words, wrestling is

a sum of spectacles, of which no single one is a function: each moment imposes

the total knowledge of a passion which rises erect and alone, without ever

extending to the crowning moment of a result.

|

|

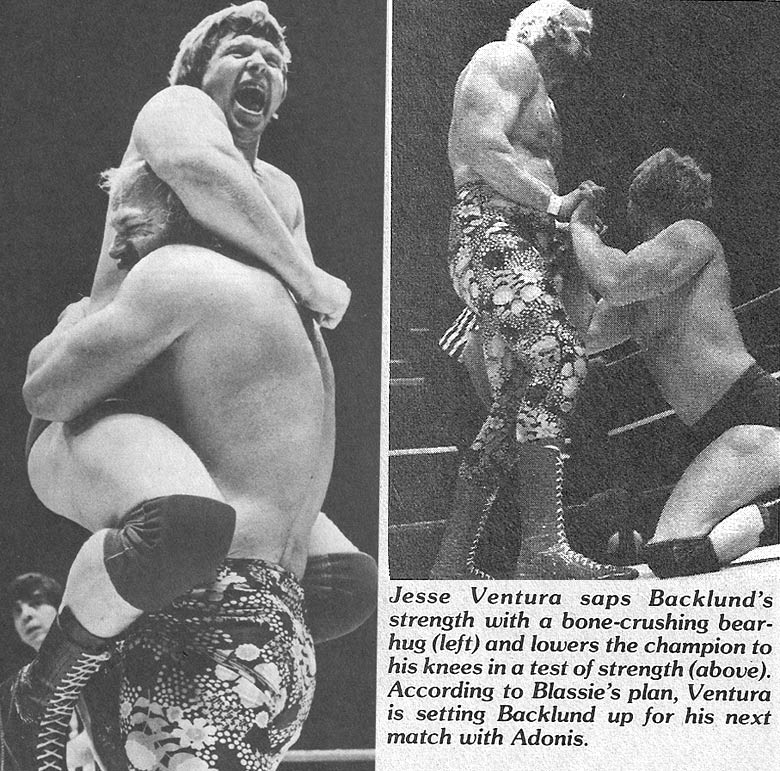

Thus the function of the wrestler

is not to win; it is to go exactly through the motions which are expected

of him.

|

It is said that judo contains

a hidden symbolic aspect; even in the midst of efficiency, its gestures

are measured, precise but restricted, drawn accurately but by a stroke

without volume.

|

|

Wrestling, on the contrary,

offers excessive gestures, exploited to the limit of their meaning.

|

|

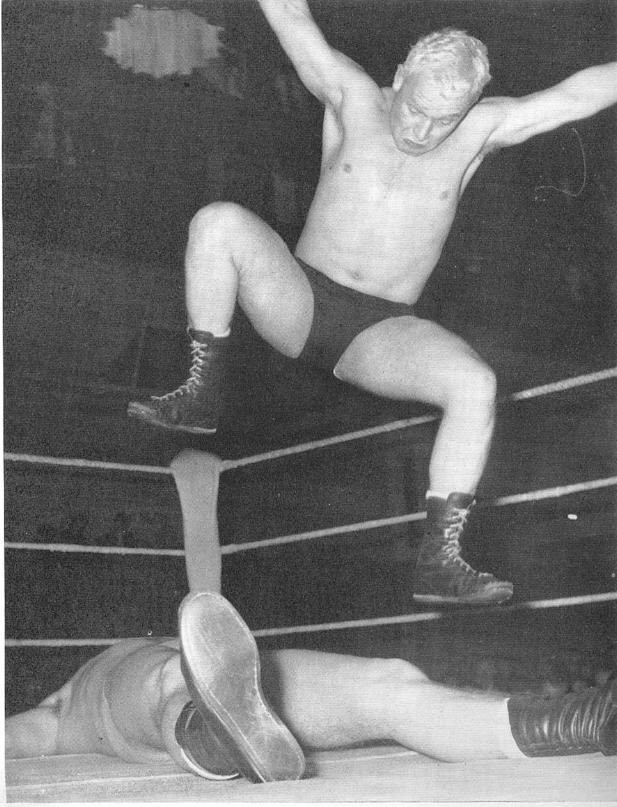

In judo, a man who is down is hardly down at all, he rolls over,

he draws back, he eludes defeat, or, if the latter is obvious, he immediately

disappears;

|

|

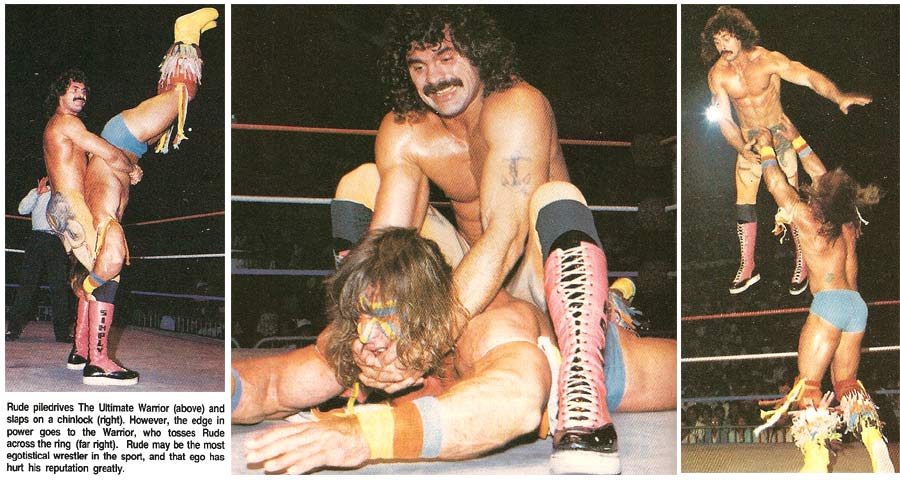

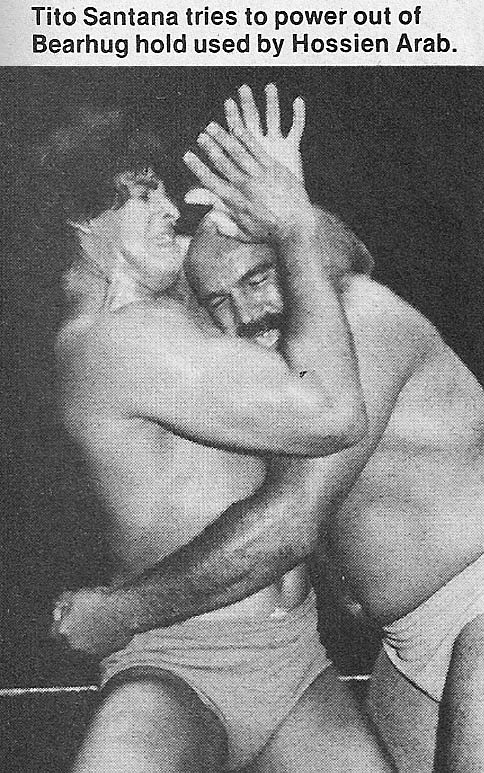

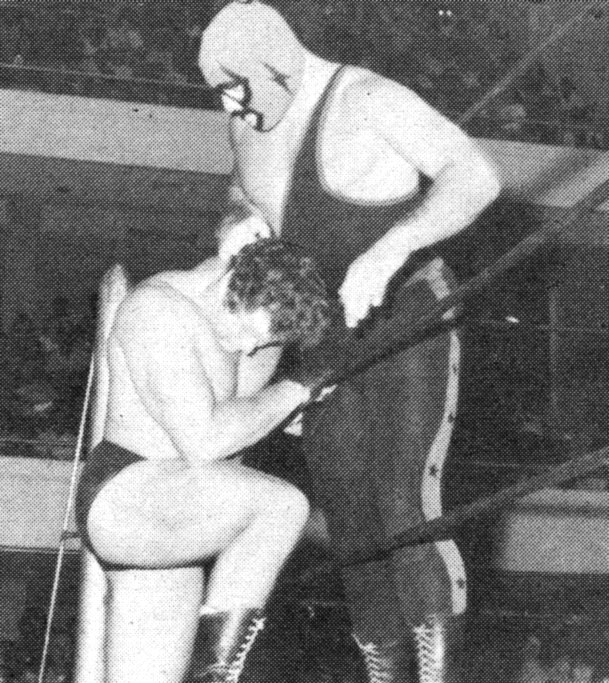

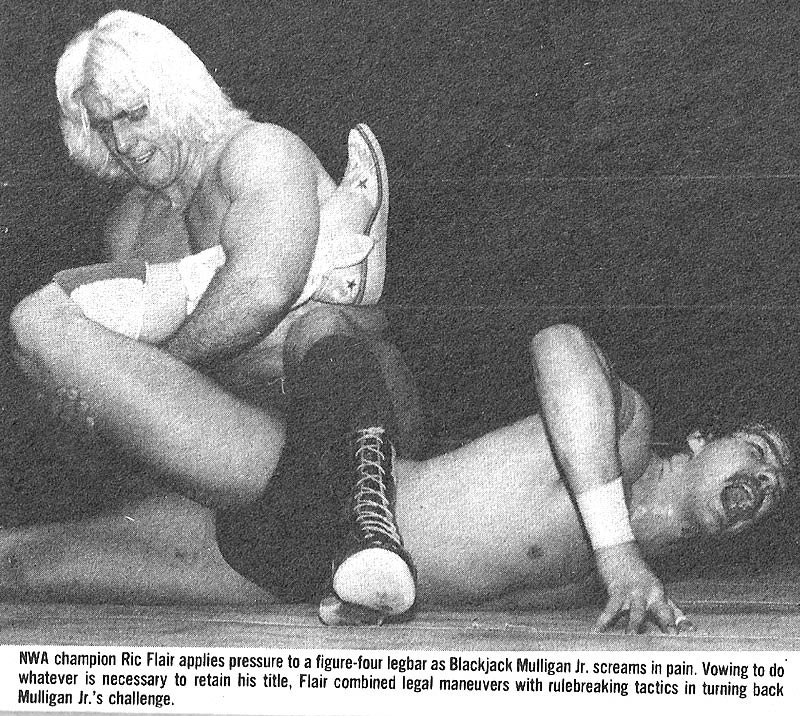

In wrestling, a man who is

down is exaggeratedly so, and completely fills the eyes of the spectators

with the intolerable spectacle of his powerlessness.

|

|

This function of grandiloquence

is indeed the same as that of ancient theater, whose principle, language

and props (masks and buskins) concurred in the exaggeratedly visible explanation

of a Necessity.

|

|

The gesture of the vanquished

wrestler signifying to the world a defeat which, far from disguising,

he emphasizes and holds like a pause in music, corresponds to the mask of

antiquity meant to signify the tragic mode of the spectacle.

|

|

|

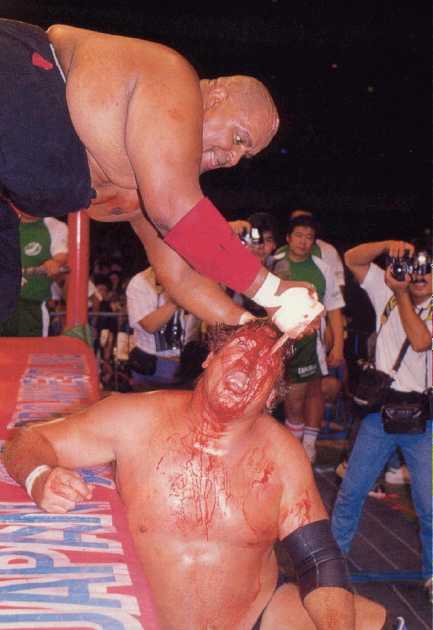

In wrestling, as on the stage

in antiquity, one is not ashamed of one's suffering, one knows how to

cry, one has a liking for tears.

|

|

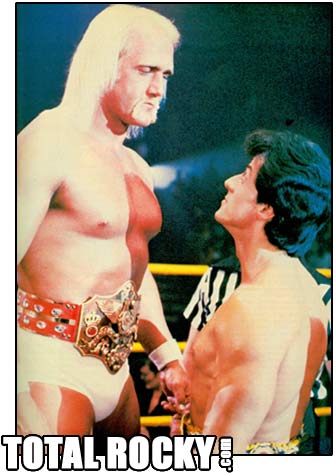

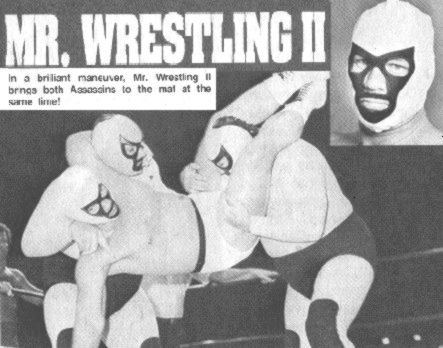

Each sign in wrestling is

therefore endowed with an absolute clarity, since one must always understand

everything on the spot. As soon as the adversaries are in the ring, the public

is overwhelmed with the obviousness of the roles.

|

|

As in the theater, each physical

type expresses to excess the part which has been assigned to the contestant.

|

|

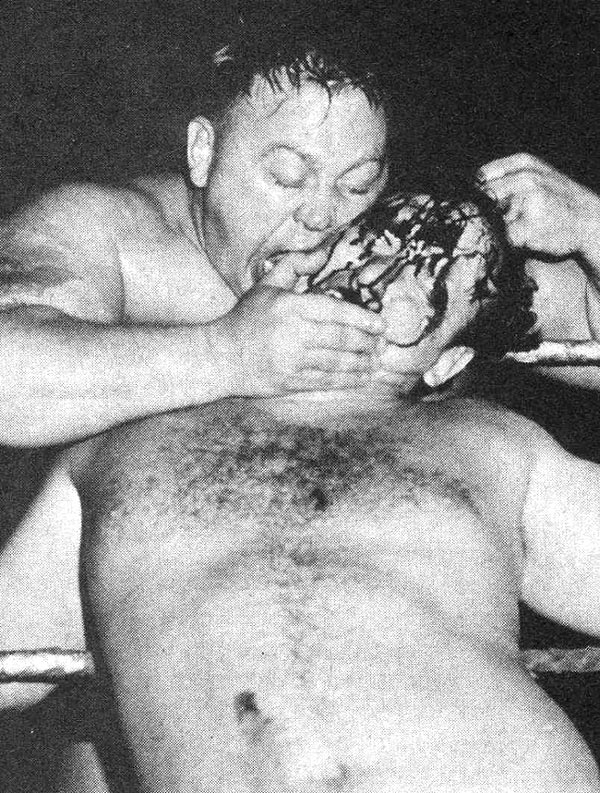

Thauvin, a fifty-year-old

with an obese and sagging body, whose type of asexual hideousness always

inspires feminine nicknames, displays in his flesh the characters of baseness,

for his part is to represent what, in the classical concept of the salaud,

the 'bastard' (the key-concept of any wrestling-match), appears as organically

repugnant.

|

The nausea voluntarily provoked

by Thauvin shows therefore a very extended use of signs: not only is ugliness

used here in order to signify baseness, but in addition ugliness is wholly

gathered into a particularly repulsive quality of matter: the pallid collapse

of dead flesh (the public calls Thauvin la barbaque, 'stinking meat').

|

|

So the passionate condemnation

of the crowd no longer stems from its judgment, but instead from the very

depth of its humours.

|

|

It will

thereafter let itself be frenetically embroiled in an idea of Thauvin which

will conform entirely with this physical origin: his actions will perfectly

correspond to the essential viscosity of his personage.

|

|

|

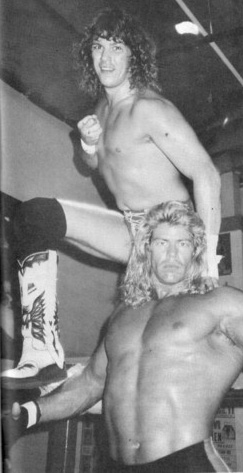

It is therefore in the body

of the wrestler that we find the first key to the contest.

|

|

I know from the start that

all of Thauvin's actions, his treacheries, cruelties and acts of cowardice,

will not fail to measure up to the first image of ignobility he gave me.

|

|

I can trust him to carry out

intelligently and to the last detail all the gestures of a kind of amorphous

baseness, and thus fill to the brim the image of the most repugnant bastard

there is: the bastard-octopus.

|

|

Wrestlers

therefore have a physique as peremptory as those of the characters of

the Commedia dell'Arte*, who display in advance, in

their costumes and attitudes, the future contents of their parts.

|

|

* [In Italy, Commedia dell'Arte

was an early form of Improv comedy, always using the same stereo-typical characters.]

|

Just as Pantaloon can never

be anything but a ridiculous cuckold, Harlequin an astute servant and the

Doctor a stupid pedant, in the same way Thauvin will never be anything

but an ignoble traitor,

|

|

Reinieres (a tall blond fellow

with a limp body and unkempt hair) the moving image of passivity,

|

|

Mazaud (short and arrogant

like a cock) that of grotesque conceit,

|

|

and Orsano (an effeminate teddy-boy

first seen in a blue- and-pink dressing-gown) that, doubly humorous, of a

vindictive salope, or bitch.

|

|

The physique of the wrestlers

therefore constitutes a basic sign, which like a seed contains the whole

fight.

|

|

|

But this seed proliferates,

for it is at every turn during the fight, in each new situation, that

the body of the wrestler casts to the public the magical entertainment

of a temperament which finds its natural expression in a gesture.

|

|

The different strata of meaning

throw light on each other, and form the most intelligible of spectacles.

|

|

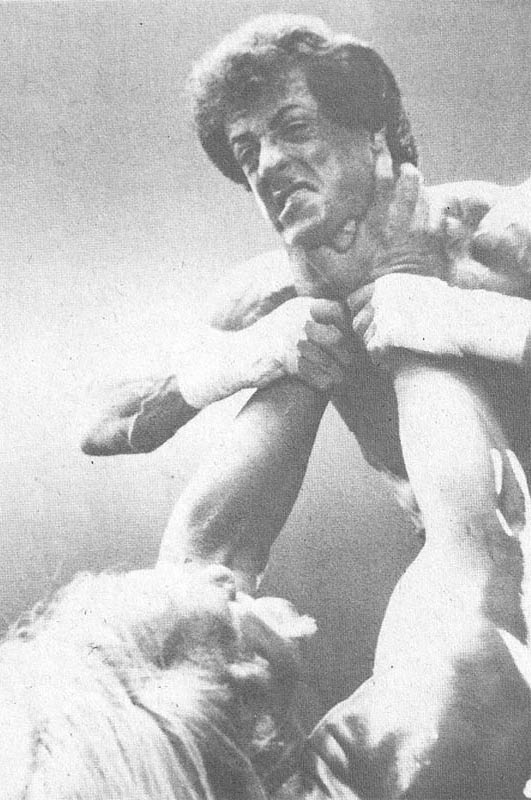

Wrestling is like a diacritic

writing: above the fundamental meaning of his body, the wrestler arranges

comments which are episodic but always opportune, and constantly help the

reading of the fight by means of gestures, attitudes and mimicry which

make the intention utterly obvious.

|

|

Sometimes the wrestler triumphs

with a repulsive sneer while kneeling on the good sportsman;

|

|

sometimes he gives the crowd

a conceited smile which forebodes an early revenge;

|

|

sometimes, pinned to the ground,

he hits the floor ostentatiously to make evident to all the intolerable

nature of his situation;

|

|

and sometimes he erects a

complicated set of signs meant to make the public understand that he legitimately

personifies the ever-entertaining image of the grumbler, enlessly confabulating

about his displeasure.

|

To

be continued...

|

|

|

|

|