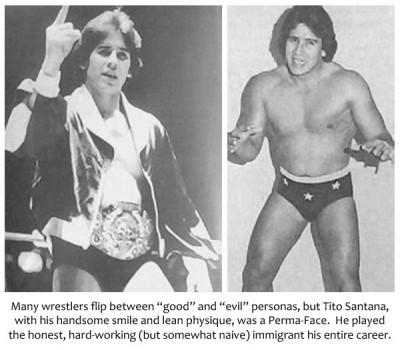

Tito Santana was a popular Good Guy wrestler in the 1980s. He was handsome and friendly, and he portrayed a humble Mexican immigrant who came to this country to struggle and make a better life, but faced constant harassment and injustice. He was one of the few wrestlers who remained a “Baby-Face” his entire career, and his habit of wearing pure white wrestling gear only added to his good-guy image.

Tito Santana was a popular Good Guy wrestler in the 1980s. He was handsome and friendly, and he portrayed a humble Mexican immigrant who came to this country to struggle and make a better life, but faced constant harassment and injustice. He was one of the few wrestlers who remained a “Baby-Face” his entire career, and his habit of wearing pure white wrestling gear only added to his good-guy image.

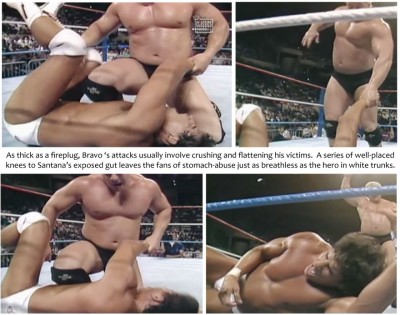

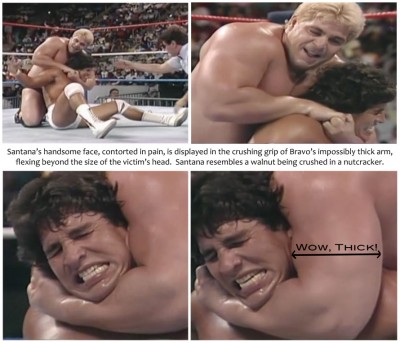

As a Mexican American, Santana represented the oppressed immigrant, the working-poor minority. You had to feel a bit sorry for him, and putting against a massive beast like Dino Bravo, whose muscles were pumped up to ridiculous proportions, seemed like exploitation of Santana. Just as many business owners import foreign workers for cheap labor while imposing horrible working conditions on them, so too are the promoters using Santana’s appealing body to entertain the crowd, like a modern-day Gladiator, through the spectacle of his pain and agony.

As a Mexican American, Santana represented the oppressed immigrant, the working-poor minority. You had to feel a bit sorry for him, and putting against a massive beast like Dino Bravo, whose muscles were pumped up to ridiculous proportions, seemed like exploitation of Santana. Just as many business owners import foreign workers for cheap labor while imposing horrible working conditions on them, so too are the promoters using Santana’s appealing body to entertain the crowd, like a modern-day Gladiator, through the spectacle of his pain and agony.

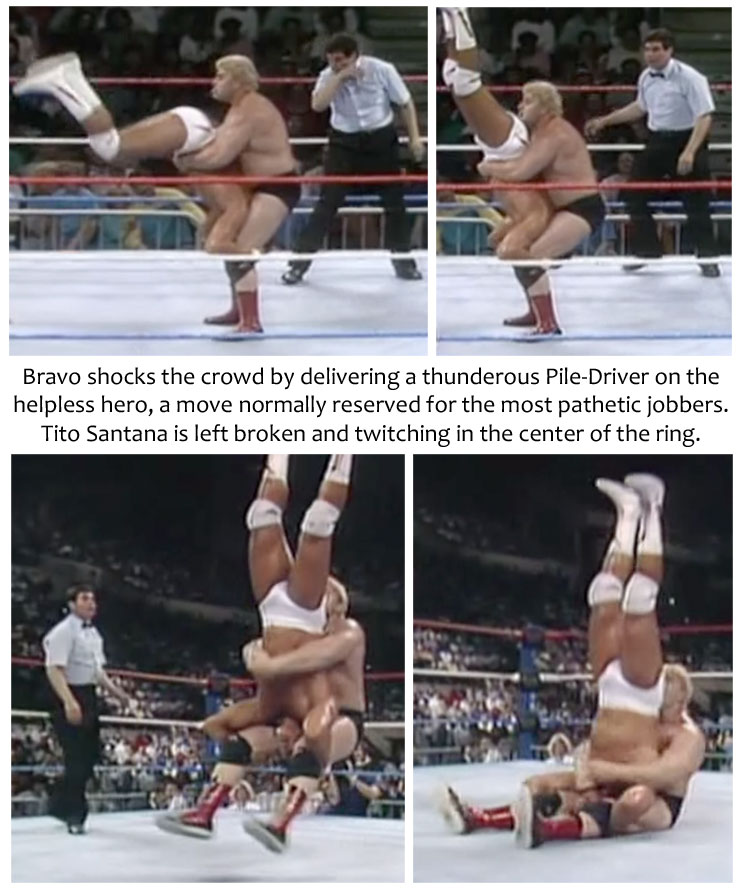

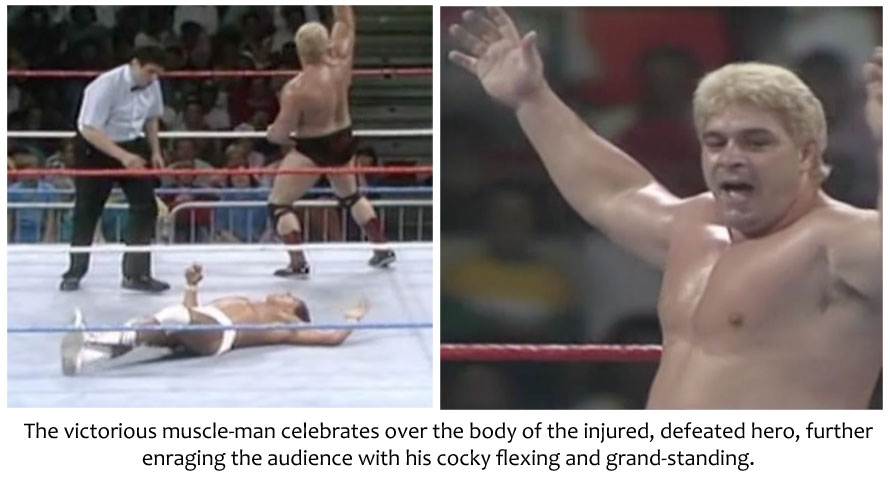

Bleach-blond Dino Bravo, with his pale, bloated body, is a symbol of the rich and dominant white culture — super-sized, cocky, and obsessed with power.

Bleach-blond Dino Bravo, with his pale, bloated body, is a symbol of the rich and dominant white culture — super-sized, cocky, and obsessed with power.

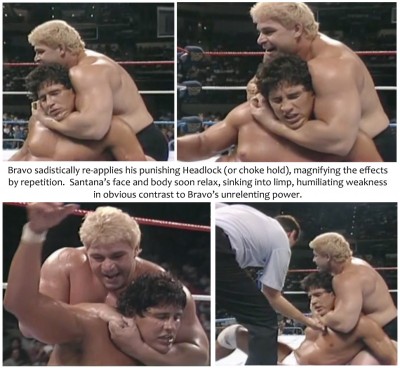

Bravo uses many crushing and choking moves on his lean, dark-skinned victim, which represent the strangling tyranny of imperialism and the crushing poverty that is faced by immigrant workers. Once again, pro wrestling is throwing our own social issues and racial hang-ups right in our faces by televising the prolonged torture of Tito Santana.

Hispanic wrestling fans are meant to identify with Santana (who looks and sounds like them) and his plight. Ever since Mexico was conquered (and symbolically raped) by Spanish invaders, and repeatedly subjugated by other Anglo nations, Mexican males have compensated for these humiliations by adopting a fierce macho attitude and remaining hyper-sensitive to acts of oppression.

Hispanic wrestling fans are meant to identify with Santana (who looks and sounds like them) and his plight. Ever since Mexico was conquered (and symbolically raped) by Spanish invaders, and repeatedly subjugated by other Anglo nations, Mexican males have compensated for these humiliations by adopting a fierce macho attitude and remaining hyper-sensitive to acts of oppression.

This match exploits those feelings of pride and machismo and fires up the passions of the Mexican men in the audience by repeatedly showing the Hispanic wrestler in agony, a huge white bicep clamped firmly around his jugular.

This match exploits those feelings of pride and machismo and fires up the passions of the Mexican men in the audience by repeatedly showing the Hispanic wrestler in agony, a huge white bicep clamped firmly around his jugular.

Jessie Ventura, announcing the match, further stirs up the hate by making crude, racist comments and calling Tito by the demeaning name of “Chico.” Either Tito was too polite and classy to demand an apology from Ventura, or he was cowed into silence by the dominant culture.

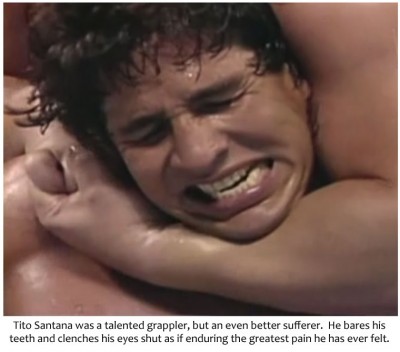

Viewers of this match will no doubt feel compassion for the down-trodden immigrant, but Santana’s performance inspires a more subtle impression that he is a comical figure, a bit of a pathetic rube. He’s so squeaky clean and gullible, it’s frustrating to watch.

Viewers of this match will no doubt feel compassion for the down-trodden immigrant, but Santana’s performance inspires a more subtle impression that he is a comical figure, a bit of a pathetic rube. He’s so squeaky clean and gullible, it’s frustrating to watch.

In his interviews and matches, he acts impossibly positive, honest, and optimistic, to the point of seeming naive. No matter how dirty his opponents fight, he never pulls hair, chokes, or claws the eyes to win a match because someone told him that would be “wrong” and he believed it. The fact that he agreed to get in the ring with a big Man-Beast like Bravo proves he is a Pollyanna — fresh off the banana boat, a born sucker.

So Santana’s performance plays on our emotions and attitudes in several ways. We feel outrage at his plight and the way minorities are mistreated and exploited. At the same time, we are frustrated by this Good-Two Shows and pity his foolish obedience to the rules. If he is this gullible and innocent, we think in the back of our minds, he deserves what he gets in the ring.

So Santana’s performance plays on our emotions and attitudes in several ways. We feel outrage at his plight and the way minorities are mistreated and exploited. At the same time, we are frustrated by this Good-Two Shows and pity his foolish obedience to the rules. If he is this gullible and innocent, we think in the back of our minds, he deserves what he gets in the ring.

So Santana is able to make us both feel sorry for him, and to also despise him. Part of us wants him to take revenge on this big cocky muscle-man, and part of us feels his punishment is justified — we are even eager to see it.

So Santana is able to make us both feel sorry for him, and to also despise him. Part of us wants him to take revenge on this big cocky muscle-man, and part of us feels his punishment is justified — we are even eager to see it.

Probably the reason Santana remained a Baby-Face during his entire career was because he was so darn good at it. He kept his hair long enough to grab in one’s fist. He kept his body as fit and tan as Tarzan. He knew how to use his expressive eyes and pouty mouth to communicate his pain.